Lee

Even if you’re not on pilgrimage, Senso-ji is an appropriate place to begin a visit to Tokyo. It’s the city’s oldest temple, dating back before the city existed, almost 1400 years to 645 AD. It’s doubtful that anything but the Sumida River remains from that time, aside from the statue of Kannon that the original temple was built to house. The brothers Hinokuma Hamanari and Hinokuma Takenari were fishing on the Sumida and caught the statue in their nets on the morning of March 18th, 628. As they were eating their breakfast, they couldn’t have imagined the city that would grow around the statue they were about to find; they couldn’t imagine us imagining them on that sunny morning.

The statue that remains as evidence of their presence on the Sumida River that day must be imagined. Shokai Shonin, the Priest who built the original temple, had a dream warning him that no one should see the statue and it was not seen again for over a thousand years until, during the Meiji period, suspicious government officials came to verify its existence. The officials opened the altar and made sketches of the statue while the monks averted their eyes. The Bodhisattva has not been seen since, but we trust s/he is there, hidden, surrounded by the city s/he founded and the hundreds of millions of lives s/he holds in her heart. A good metaphor for faith.

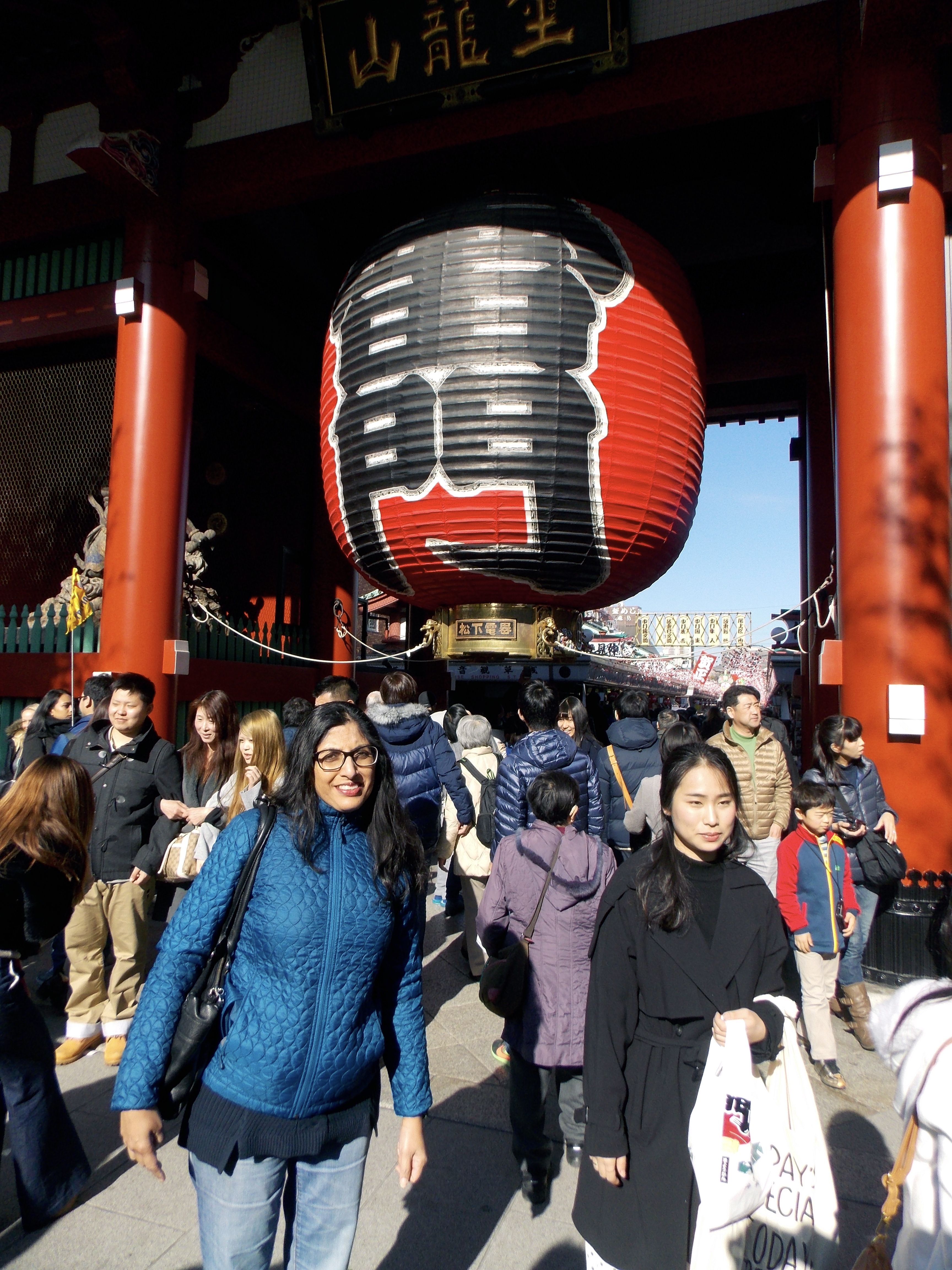

The trains aren’t crowded on this 30th of December, and when we exit the subway we have no trouble finding the temple: signs everywhere point the way. By the time we reach the enormous red-and-black Japanese lantern of Kaminarimon, “The Thunder Gate”, we are submerged in a sea of humanity. On any given day Senso-ji is a popular spot, attracting 30 million visitors each year, but today is only one day before New Year’s Eve. Coming as I do from a farm in Saskatchewan I feel as though I’m surrounded by all 30 million. At least I’m taller than average, whereas Ranjini sinks into the crowd. Nervous that I’ll lose her, I grasp her hand and we follow the procession through The Kaminarimon Gate, imitating the others who reach up and touch the dragon carving fitted into its base. I suspect we’re doing this for luck.

Once through, we swim with the crowd up Nakamise-dori, slowly approaching the temple. This narrow street, lined on both sides with a multitude of stalls selling food, crafts, kimonos and t-shirts, cheap and expensive souvenirs, makes me realize that pilgrimage is about more than faith. It’s about separating the pilgrims from their money. I don’t voice this to Ranjini, knowing she won’t appreciate the cynicism of this sentiment, but it is undeniable that the economy created by the pilgrimage is, perhaps, as important in understanding it as faith. Money may not make the world go round, but it does make people gather, and it creates cities and civilizations. All that is made manifest in the crowd pressing against us as we edge our way toward the Hozomon Gate.

Hozomon means “Treasure House” and this gate marks the boundary between the profane world of commerce and the actual temple grounds. Two Nio statues guard the gate, and the 2nd floor of the treasure house contains ancient copies of the lotus sutra and the Issai-kyo, an ancient manuscript of Buddha’s teachings. We stop at a stall near the Hozomon Gate, where a nun sells incense for 100 Yen, and ask where to buy our go-shuin book. These are used to record the visit to each temple: a monk or lay-worker stamps a page and adds beautiful calligraphy that contains a mantra, the date, and the temple’s name. The nun draws a map and Ranjini buys and lights some incense, leaving it as an offering in the huge metal incense burner. She flutters her hands like birds to direct the smoke over her body and bows to the beautiful young Buddha.

Ranjini

After Marie introduced me to Kuan Yin, I was confused by my overwhelming devotion to an unknown goddess. One night after I prayed to Kannon—“Am I on the right path?”—I dreamed of her.

She stood before me. “Hello, I’m Kuan Yin.”

She was in her thirties, medium-height, beautiful, slender, dressed in gray robes, her black hair coiled in a topknot.

“You must be very busy,” I said.

She smiled at my words. “Yes,” she said, before taking off, one leg gracefully folded like an Indian goddess, flying like a dakini into the air.

I am used to crowds but I sense Lee’s difficulty as we press forward to the ancient temple of Senso-ji. Since that dream encounter, I have been on pilgrimage. Yet, this is my first formalized pilgrimage with 33-stops and a go-shuin book. In the souvenir stalls, there are no postcards of the ancient (and hidden) Kannon statue that we have come to visit; there is not even a replica of her in the main shrine room.

In the foyer outside the main shrine, we bow to the deities through the glass and light candles and buy good luck charms. I slip off my shoes and attempt to gain entrance into the main hall but a monk politely gestures me out.

There seems to be no way to meet Kannon.

I know that she is here, infinite, vast, limitless, endlessly compassionate, and it is silly this yearning to touch, to take home, or at the least, to see.

At Sensoji, I shake the cylindrical container. Simultaneously, thousands of pilgrims address the goddess. Yes, Kannon is very busy.

Oracle number 18, Good Fortune.

The linen robe turns into a green one. What you’ve been troubled for a long time will soon begin to fade away. Your virtue and happiness will reveal themselves. Your wishes will be realized. Building a new house and removal are good. Marriage and employment are all good.

Outside, white slips of oracles flutter on innumerable stands. In Japanese temples, everything seems left behind, candles and wooden plaques with inscribed prayers. Yet, I tuck my oracle into my purse.

As we prepare to leave Senso-ji, I return to the incense burner where smoke rises in thick clouds, and direct the smoke to my heart for healing and purification.

Let go.

I tie my good oracle to the stand.

It is only later that I am told that good oracles are kept, and the bad ones left behind for Kannon’s mitigation.

Lee, my Love. Kanzeon Bosatsu. This now is blessed and joyous.

At the beginning of the new millennium Dad started building an addition onto the northwest bedroom (which used to be Ray’s and mine), with a plan to make it into a display room for his gramophones. The addition cut off the staircase to the roof, which was no longer functional anyway.

At the beginning of the new millennium Dad started building an addition onto the northwest bedroom (which used to be Ray’s and mine), with a plan to make it into a display room for his gramophones. The addition cut off the staircase to the roof, which was no longer functional anyway. Dad was diagnosed with asbestosis before he could complete the plan. What was it John Lennon said in that song about his beautiful son? “Life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans.” Or, eventually, death is what happens to you.

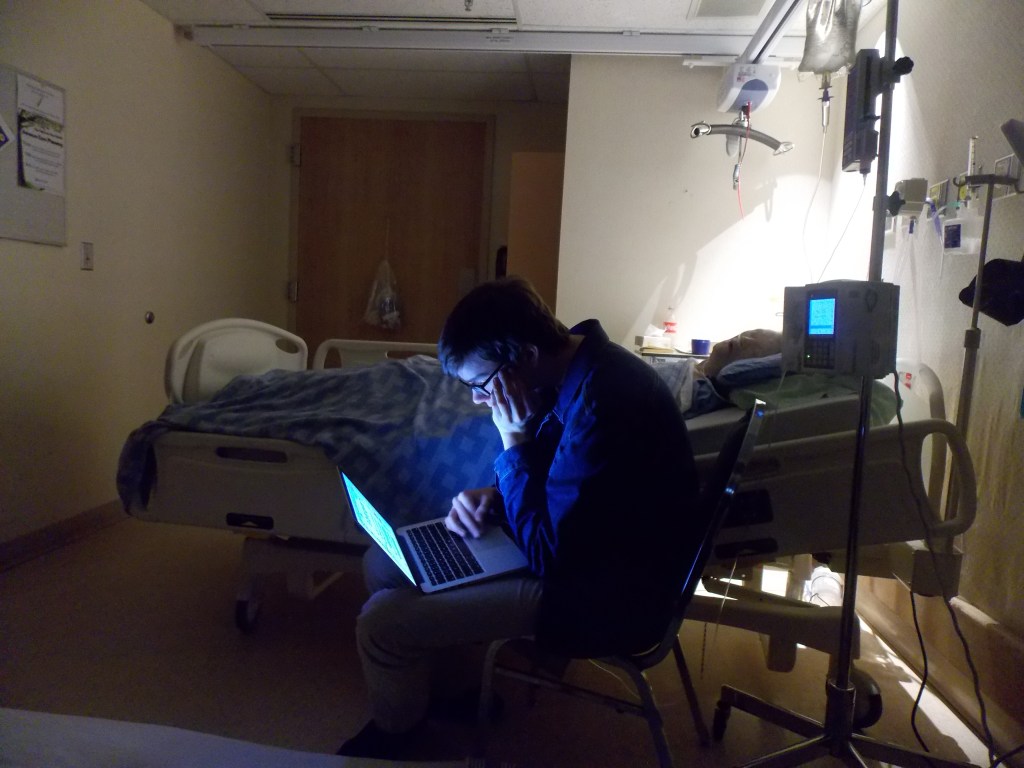

Dad was diagnosed with asbestosis before he could complete the plan. What was it John Lennon said in that song about his beautiful son? “Life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans.” Or, eventually, death is what happens to you. When I started this…thing–I suppose it’s a blog, but I like to think of it as a story with pictures–I conceived it as a way of talking about impermanence and loss: about losing my father, and losing my youth, all of which is tied up in that house. Dad grew up and died there and it still stands, somehow physically containing all of those memories: his memories and my memories and the memories of everyone who lived there.

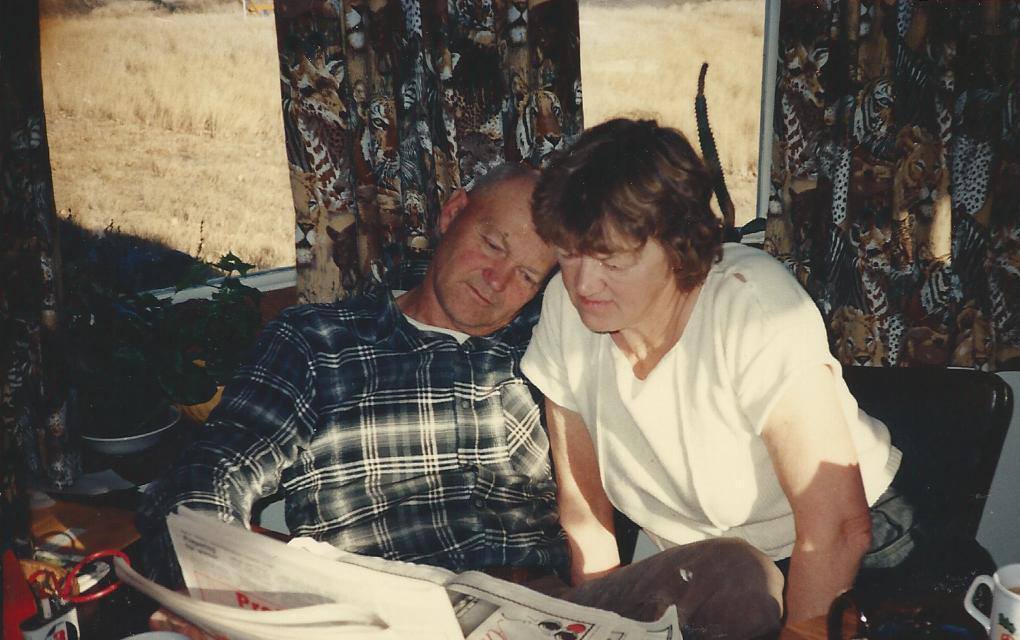

When I started this…thing–I suppose it’s a blog, but I like to think of it as a story with pictures–I conceived it as a way of talking about impermanence and loss: about losing my father, and losing my youth, all of which is tied up in that house. Dad grew up and died there and it still stands, somehow physically containing all of those memories: his memories and my memories and the memories of everyone who lived there. While I was writing this thing, we lost my mother, and it became about that loss too. Last June, the day after she died, we all went home to the farm and I climbed up on the roof and took these photos. When I look at the tin roof over the kitchen I can’t help but think of lying in bed listening to the patter the rain made against that tin. And I can’t help but think that maybe this would be a good place to end.

While I was writing this thing, we lost my mother, and it became about that loss too. Last June, the day after she died, we all went home to the farm and I climbed up on the roof and took these photos. When I look at the tin roof over the kitchen I can’t help but think of lying in bed listening to the patter the rain made against that tin. And I can’t help but think that maybe this would be a good place to end. After all, if it’s a story it needs an ending. Problem is, I’ve never been good with endings. Maybe too much of that Modernist sensibility in me that endings should be ambiguous in order to accurately reflect reality–the problem being that most readers end up thinking, “What was that all about?” and tell the next reader that it just wasn’t worth it in the end. Or simply shake their heads and say nothing at all.

After all, if it’s a story it needs an ending. Problem is, I’ve never been good with endings. Maybe too much of that Modernist sensibility in me that endings should be ambiguous in order to accurately reflect reality–the problem being that most readers end up thinking, “What was that all about?” and tell the next reader that it just wasn’t worth it in the end. Or simply shake their heads and say nothing at all. So what was it all about? What is it all about? I guess if I had to say, I would say it is about how my father and my mother taught us the importance of making beautiful things. Or trying, at least. Human things, beautiful at times in their ugliness and in their mistakes. Just do your best to make those things as beautiful as you possibly can. There is not so much to regret in a life dedicated to the making of beautiful things.

So what was it all about? What is it all about? I guess if I had to say, I would say it is about how my father and my mother taught us the importance of making beautiful things. Or trying, at least. Human things, beautiful at times in their ugliness and in their mistakes. Just do your best to make those things as beautiful as you possibly can. There is not so much to regret in a life dedicated to the making of beautiful things.

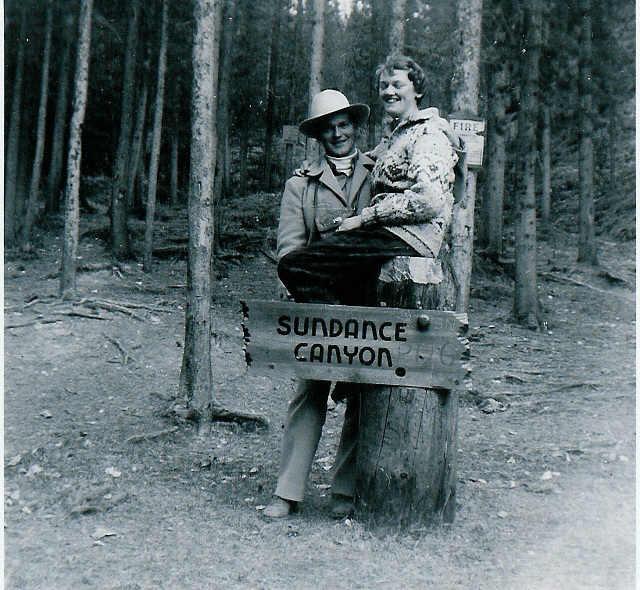

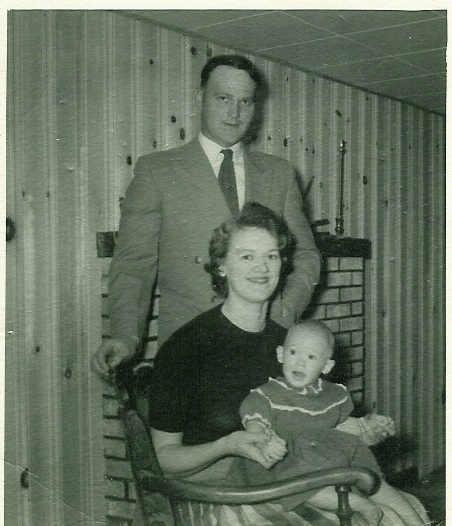

Vital Monette was barely a man when he met Shirley: only eighteen, she being the older woman. Carmel had already run off to join the circus, so he didn’t have to deal much with her direct animosity, but there was still the rest of the Gowan family: Irish Protestant Orange stock who were more than a little suspicious of his French Catholic roots. In spite of the less than enthusiastic reception, they married and moved into my father’s house, then still my grandfather’s house, where the family could keep a close eye on him. They likely suspected he was one of those fabled latin lovers who would run off and leave Shirley the first chance he got.

Vital Monette was barely a man when he met Shirley: only eighteen, she being the older woman. Carmel had already run off to join the circus, so he didn’t have to deal much with her direct animosity, but there was still the rest of the Gowan family: Irish Protestant Orange stock who were more than a little suspicious of his French Catholic roots. In spite of the less than enthusiastic reception, they married and moved into my father’s house, then still my grandfather’s house, where the family could keep a close eye on him. They likely suspected he was one of those fabled latin lovers who would run off and leave Shirley the first chance he got.

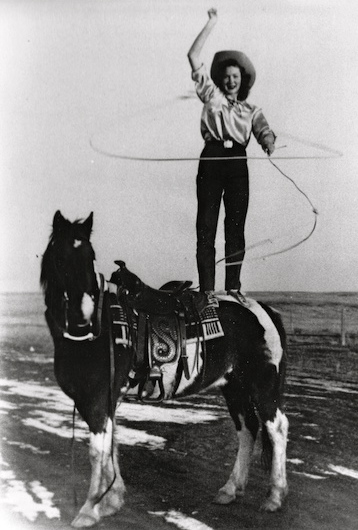

Flash-forward a few thousand years and around the globe to Saskatchewan in 1924.

Flash-forward a few thousand years and around the globe to Saskatchewan in 1924.