Page wire helps keep the beavers out of Gowan’s Grove, but some always manage to sneak in and cut down trees, just as they’d demolished my Uncle Gordon’s grove. It took fifty years to grow these precious trees on the bald prairie. We grew up protecting them. I remember cold nights beside the creek with my father, cradling rifles in our arms, waiting.

One morning last summer I got up at eight, crawled out of the tent, and walked straight down to see whether Ray had caught another beaver. He had. Got it headfirst, by the neck, as it was attempting to leave with a small twig of poplar in its mouth. When Ray arrived we puzzled over this, looking for a place it might have penetrated the fence without crawling through the trap.

“Nothing about it makes any sense,” Ray said. There was no way it could have passed through the Conibear trap and into the Grove without tripping the wire. We couldn’t find another place it might have entered. We reasoned that it may have already been inside when he arrived last night to set the trap, and managed to hide when it heard him coming. Doubtful as it seemed (especially since we couldn’t find any sign of it chewing any trees except the branches he’d left for bait at the opening) it was the only possible explanation.

Once Ray had removed it from the trap we each grabbed a leg and carried it to the truck. Its musk was strong and it was large, but smaller than others he’d caught before, he told me. One recently was big enough he couldn’t carry it by himself and was forced to drag it in short bursts. We dumped it in the back of his red pick-up and he drove up to the house, where he threw it in the deep-freeze in the garage. A friend of his would use it as bait for hunting black bear.

I realize that this will all seem cruel to many, but I hope that they will also recognize a connection to nature that is now often lacking, and a respect that can only really exist with direct contact and the conflict that proximity naturally brings.

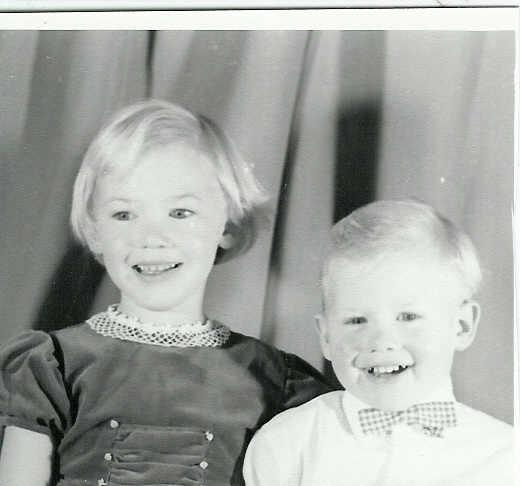

When my father was born on Christmas Eve 1929, my grandparents were not only facing the loss of their house, built just a couple of year’s before; the world had also just endured the stock market crash. I have no idea whether my grandfather had any investments aside from his land and cattle. He may have believed that people trading pieces of paper in New York and Chicago and London and Toronto and Winnipeg had little to do with his life, but he would discover that they did when the market for his grain and his cattle dried up completely in the coming years.

When my father was born on Christmas Eve 1929, my grandparents were not only facing the loss of their house, built just a couple of year’s before; the world had also just endured the stock market crash. I have no idea whether my grandfather had any investments aside from his land and cattle. He may have believed that people trading pieces of paper in New York and Chicago and London and Toronto and Winnipeg had little to do with his life, but he would discover that they did when the market for his grain and his cattle dried up completely in the coming years.

A thin layer of plaster dust partly covers the wood-grain Formica that covers the table. Someone, probably my brother Ray, started mudding a spot of water damage on the ceiling almost directly over my head; got so far as sanding, but it looks as though it needs more mud, or perhaps the water that damaged it in the first place is still getting in, and the job was abandoned until the roof is fixed.

A thin layer of plaster dust partly covers the wood-grain Formica that covers the table. Someone, probably my brother Ray, started mudding a spot of water damage on the ceiling almost directly over my head; got so far as sanding, but it looks as though it needs more mud, or perhaps the water that damaged it in the first place is still getting in, and the job was abandoned until the roof is fixed.